Pumps

This page provides the chapters on pumps from the "DOE Fundamentals Handbook: Mechanical Science," DOE-HDBK-1018/1-93, U.S. Department of Energy, Jan 1993.

Other related chapters from the "DOE Fundamentals Handbook: Mechanical Science" can be seen to the right.

- Pumps

- Valves

Centrifugal Pumps

Centrifugal pumps are the most common type of pumps found in DOE facilities. Centrifugal pumps enjoy widespread application partly due to their ability to operate over a wide range of flow rates and pump heads.

Introduction

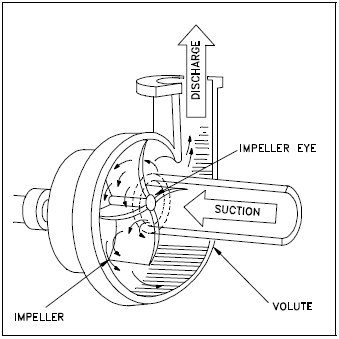

Centrifugal pumps basically consist of a stationary pump casing and an impeller mounted on a rotating shaft. The pump casing provides a pressure boundary for the pump and contains channels to properly direct the suction and discharge flow. The pump casing has suction and discharge penetrations for the main flow path of the pump and normally has small drain and vent fittings to remove gases trapped in the pump casing or to drain the pump casing for maintenance.

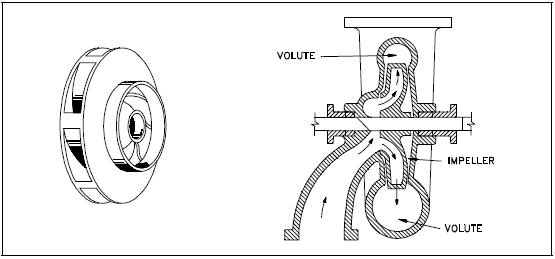

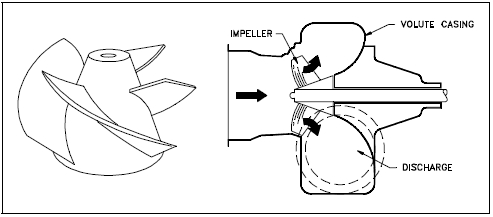

Figure 1 is a simplified diagram of a typical centrifugal pump that shows the relative locations of the pump suction, impeller, volute, and discharge. The pump casing guides the liquid from the suction connection to the center, or eye, of the impeller. The vanes of the rotating impeller impart a radial and rotary motion to the liquid, forcing it to the outer periphery of the pump casing where it is collected in the outer part of the pump casing called the volute. The volute is a region that expands in cross-sectional area as it wraps around the pump casing. The purpose of the volute is to collect the liquid discharged from the periphery of the impeller at high velocity and gradually cause a reduction in fluid velocity by increasing the flow area. This converts the velocity head to static pressure. The fluid is then discharged from the pump through the discharge connection.

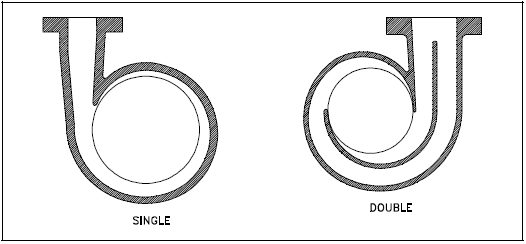

Centrifugal pumps can also be constructed in a manner that results in two distinct volutes, each receiving the liquid that is discharged from a 180° region of the impeller at any given time. Pumps of this type are called double volute pumps (they may also be referred to a split volute pumps). In some applications the double volute minimizes radial forces imparted to the shaft and bearings due to imbalances in the pressure around the impeller. A comparison of single and double volute centrifugal pumps is shown on Figure 2.

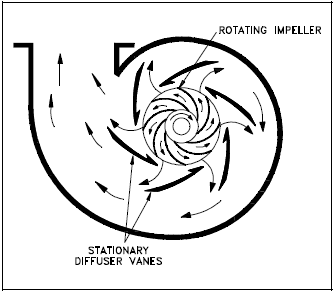

Diffuser

Some centrifugal pumps contain diffusers. A diffuser is a set of stationary vanes that surround the impeller. The purpose of the diffuser is to increase the efficiency of the centrifugal pump by allowing a more gradual expansion and less turbulent area for the liquid to reduce in velocity. The diffuser vanes are designed in a manner that the liquid exiting the impeller will encounter an ever-increasing flow area as it passes through the diffuser. This increase in flow area causes a reduction in flow velocity, converting kinetic energy into flow pressure.

Impeller Classification

Impellers of pumps are classified based on the number of points that the liquid can enter the impeller and also on the amount of webbing between the impeller blades.

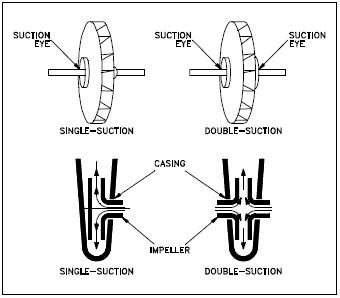

Impellers can be either single-suction or double-suction. A single-suction impeller allows liquid to enter the center of the blades from only one direction. A double-suction impeller allows liquid to enter the center of the impeller blades from both sides simultaneously. Figure 4 shows simplified diagrams of single and double-suction impellers.

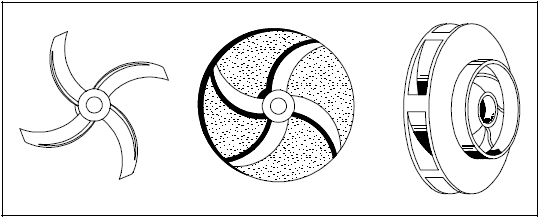

Impellers can be open, semi-open, or enclosed. The open impeller consists only of blades attached to a hub. The semi-open impeller is constructed with a circular plate (the web) attached to one side of the blades. The enclosed impeller has circular plates attached to both sides of the blades. Enclosed impellers are also referred to as shrouded impellers. Figure 5 illustrates examples of open, semi-open, and enclosed impellers.

The impeller sometimes contains balancing holes that connect the space around the hub to the suction side of the impeller. The balancing holes have a total cross-sectional area that is considerably greater than the cross-sectional area of the annular space between the wearing ring and the hub. The result is suction pressure on both sides of the impeller hub, which maintains a hydraulic balance of axial thrust.

Centrifugal Pump Classification by Flow

Centrifugal pumps can be classified based on the manner in which fluid flows through the pump. The manner in which fluid flows through the pump is determined by the design of the pump casing and the impeller. The three types of flow through a centrifugal pump are radial flow, axial flow, and mixed flow.

Radial Flow Pumps

In a radial flow pump, the liquid enters at the center of the impeller and is directed out along the impeller blades in a direction at right angles to the pump shaft. The impeller of a typical radial flow pump and the flow through a radial flow pump are shown in Figure 6.

Axial Flow Pumps

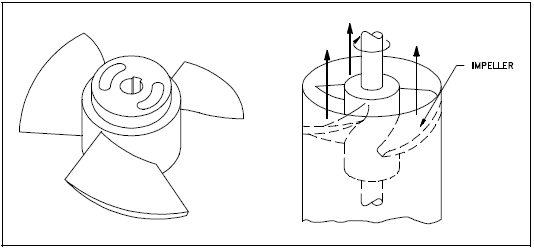

In an axial flow pump, the impeller pushes the liquid in a direction parallel to the pump shaft. Axial flow pumps are sometimes called propeller pumps because they operate essentially the same as the propeller of a boat. The impeller of a typical axial flow pump and the flow through a radial flow pump are shown in Figure 7.

Mixed Flow Pumps

Mixed flow pumps borrow characteristics from both radial flow and axial flow pumps. As liquid flows through the impeller of a mixed flow pump, the impeller blades push the liquid out away from the pump shaft and to the pump suction at an angle greater than 90°. The impeller of a typical mixed flow pump and the flow through a mixed flow pump are shown in Figure 8.

Multi-Stage Centrifugal Pumps

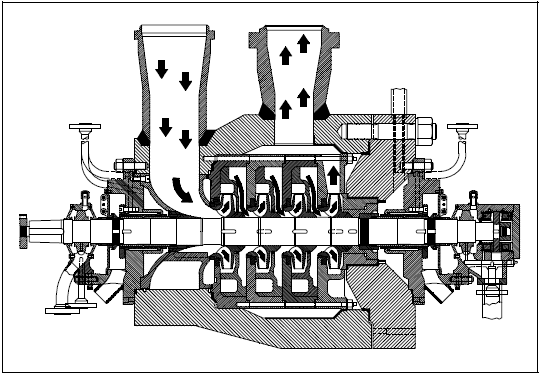

A centrifugal pump with a single impeller that can develop a differential pressure of more than 150 psid between the suction and the discharge is difficult and costly to design and construct. A more economical approach to developing high pressures with a single centrifugal pump is to include multiple impellers on a common shaft within the same pump casing. Internal channels in the pump casing route the discharge of one impeller to the suction of another impeller. Figure 9 shows a diagram of the arrangement of the impellers of a four-stage pump. The water enters the pump from the top left and passes through each of the four impellers in series, going from left to right. The water goes from the volute surrounding the discharge of one impeller to the suction of the next impeller.

A pump stage is defined as that portion of a centrifugal pump consisting of one impeller and its associated components. Most centrifugal pumps are single-stage pumps, containing only one impeller. A pump containing seven impellers within a single casing would be referred to as a seven-stage pump or, or generally, as a multi-stage pump.

Centrifugal Pump Components

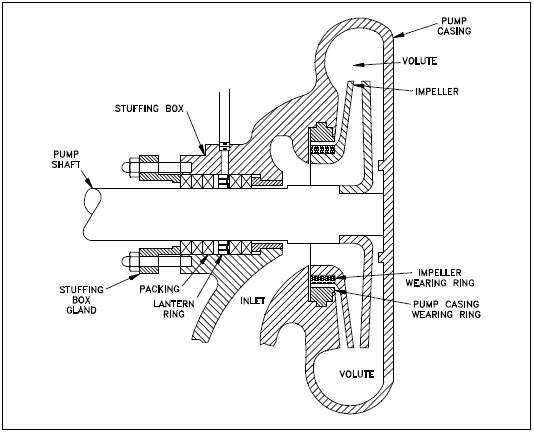

Centrifugal pumps vary in design and construction from simple pumps with relatively few parts to extremely complicated pumps with hundreds of individual parts. Some of the most common components found in centrifugal pumps are wearing rings, stuffing boxes, packing, and lantern rings. These components are shown in Figure 10 and described on the following pages.

Wearing Rings

Centrifugal pumps contain rotating impellers within stationary pump casings. To allow the impeller to rotate freely within the pump casing, a small clearance is designed to be maintained between the impeller and the pump casing. To maximize the efficiency of a centrifugal pump, it is necessary to minimize the amount of liquid leaking through this clearance from the high pressure or discharge side of the pump back to the low pressure or suction side.

Some wear or erosion will occur at the point where the impeller and the pump casing nearly come into contact. This wear is due to the erosion caused by liquid leaking through this tight clearance and other causes. As wear occurs, the clearances become larger and the rate of leakage increases. Eventually, the leakage could become unacceptably large and maintenance would be required on the pump.

To minimize the cost of pump maintenance, many centrifugal pumps are designed with wearing rings. Wearing rings are replaceable rings that are attached to the impeller and/or the pump casing to allow a small running clearance between the impeller and the pump casing without causing wear of the actual impeller or pump casing material. These wearing rings are designed to be replaced periodically during the life of a pump and prevent the more costly replacement of the impeller or the casing.

Stuffing Box

In almost all centrifugal pumps, the rotating shaft that drives the impeller penetrates the pressure boundary of the pump casing. It is important that the pump is designed properly to control the amount of liquid that leaks along the shaft at the point that the shaft penetrates the pump casing. There are many different methods of sealing the shaft penetration of the pump casing. Factors considered when choosing a method include the pressure and temperature of the fluid being pumped, the size of the pump, and the chemical and physical characteristics of the fluid being pumped.

One of the simplest types of shaft seal is the stuffing box. The stuffing box is a cylindrical space in the pump casing surrounding the shaft. Rings of packing material are placed in this space. Packing is material in the form of rings or strands that is placed in the stuffing box to form a seal to control the rate of leakage along the shaft. The packing rings are held in place by a gland. The gland is, in turn, held in place by studs with adjusting nuts. As the adjusting nuts are tightened, they move the gland in and compress the packing. This axial compression causes the packing to expand radially, forming a tight seal between the rotating shaft and the inside wall of the stuffing box.

The high speed rotation of the shaft generates a significant amount of heat as it rubs against the packing rings. If no lubrication and cooling are provided to the packing, the temperature of the packing increases to the point where damage occurs to the packing, the pump shaft, and possibly nearby pump bearings. Stuffing boxes are normally designed to allow a small amount of controlled leakage along the shaft to provide lubrication and cooling to the packing. The leakage rate can be adjusted by tightening and loosening the packing gland.

Lantern Ring

It is not always possible to use a standard stuffing box to seal the shaft of a centrifugal pump. The pump suction may be under a vacuum so that outward leakage is impossible or the fluid may be too hot to provide adequate cooling of the packing. These conditions require a modification to the standard stuffing box.

One method of adequately cooling the packing under these conditions is to include a lantern ring. A lantern ring is a perforated hollow ring located near the center of the packing box that receives relatively cool, clean liquid from either the discharge of the pump or from an external source and distributes the liquid uniformly around the shaft to provide lubrication and cooling. The fluid entering the lantern ring can cool the shaft and packing, lubricate the packing, or seal the joint between the shaft and packing against leakage of air into the pump in the event the pump suction pressure is less than that of the atmosphere.

Mechanical Seals

In some situations, packing material is not adequate for sealing the shaft. One common alternative method for sealing the shaft is with mechanical seals. Mechanical seals consist of two basic parts, a rotating element attached to the pump shaft and a stationary element attached to the pump casing. Each of these elements has a highly polished sealing surface. The polished faces of the rotating and stationary elements come into contact with each other to form a seal that prevents leakage along the shaft.

Centrifugal Pump Operation

Improper operation of centrifugal pumps can result in damage to the pump and loss of function of the system that the pump is installed in. It is helpful to know what conditions can lead to pump damage to allow better understanding of pump operating procedures and how the procedures aid the operator in avoiding pump damage.

Introduction

Many centrifugal pumps are designed in a manner that allows the pump to operate continuously for months or even years. These centrifugal pumps often rely on the liquid that they are pumping to provide cooling and lubrication to the pump bearings and other internal components of the pump. If flow through the pump is stopped while the pump is still operating, the pump will no longer be adequately cooled and the pump can quickly become damaged. Pump damage can also result from pumping a liquid whose temperature is close to saturated conditions.

Cavitation

The flow area at the eye of the pump impeller is usually smaller than either the flow area of the pump suction piping or the flow area through the impeller vanes. When the liquid being pumped enters the eye of a centrifugal pump, the decrease in flow area results in an increase in flow velocity accompanied by a decrease in pressure. The greater the pump flow rate, the greater the pressure drop between the pump suction and the eye of the impeller. If the pressure drop is large enough, or if the temperature is high enough, the pressure drop may be sufficient to cause the liquid to flash to vapor when the local pressure falls below the saturation pressure for the fluid being pumped. Any vapor bubbles formed by the pressure drop at the eye of the impeller are swept along the impeller vanes by the flow of the fluid. When the bubbles enter a region where local pressure is greater than saturation pressure farther out the impeller vane, the vapor bubbles abruptly collapse. This process of the formation and subsequent collapse of vapor bubbles in a pump is called cavitation.

Cavitation in a centrifugal pump has a significant effect on pump performance. Cavitation degrades the performance of a pump, resulting in a fluctuating flow rate and discharge pressure. Cavitation can also be destructive to pumps internal components. When a pump cavitates, vapor bubbles form in the low pressure region directly behind the rotating impeller vanes. These vapor bubbles then move toward the oncoming impeller vane, where they collapse and cause a physical shock to the leading edge of the impeller vane. This physical shock creates small pits on the leading edge of the impeller vane. Each individual pit is microscopic in size, but the cumulative effect of millions of these pits formed over a period of hours or days can literally destroy a pump impeller. Cavitation can also cause excessive pump vibration, which could damage pump bearings, wearing rings, and seals.

A small number of centrifugal pumps are designed to operate under conditions where cavitation is unavoidable. These pumps must be specially designed and maintained to withstand the small amount of cavitation that occurs during their operation. Most centrifugal pumps are not designed to withstand sustained cavitation.

Noise is one of the indications that a centrifugal pump is cavitating. A cavitating pump can sound like a can of marbles being shaken. Other indications that can be observed from a remote operating station are fluctuating discharge pressure, flow rate, and pump motor current. Methods to stop or prevent cavitation are presented in the following paragraphs.

Net Positive Suction Head

To avoid cavitation in centrifugal pumps, the pressure of the fluid at all points within the pump must remain above saturation pressure. The quantity used to determine if the pressure of the liquid being pumped is adequate to avoid cavitation is the net positive suction head (NPSH). The net positive suction head available (NPSHA) is the difference between the pressure at the suction of the pump and the saturation pressure for the liquid being pumped. The net positive suction head required (NPSHR) is the minimum net positive suction head necessary to avoid cavitation.

The condition that must exist to avoid cavitation is that the net positive suction head available must be greater than or equal to the net positive suction head required. This requirement can be stated mathematically as shown below.

A formula for NPSHA can be stated as the following equation.

When a centrifugal pump is taking suction from a tank or other reservoir, the pressure at the suction of the pump is the sum of the absolute pressure at the surface of the liquid in the tank plus the pressure due to the elevation difference between the surface of liquid in the tank and the pump suction less the head losses due to friction in the suction line from the tank to the pump.

Where:

| NPSHA = net positive suction head available |

| Pa = absolute pressure on the surface of the liquid |

| Pst = pressure due to elevation between liquid surface and pump suction |

| hf = head losses in the pump suction piping |

| Psat = saturation pressure of the liquid being pumped |

Preventing Cavitation

If a centrifugal pump is cavitating, several changes in the system design or operation may be necessary to increase the NPSHA above the NPSHR and stop the cavitation. One method for increasing the NPSHA is to increase the pressure at the suction of the pump. For example, if a pump is taking suction from an enclosed tank, either raising the level of the liquid in the tank or increasing the pressure in the space above the liquid increases suction pressure.

It is also possible to increase the NPSHA by decreasing the temperature of the liquid being pumped. Decreasing the temperature of the liquid decreases the saturation pressure, causing NPSHA to increase. Recall from the previous module on heat exchangers that large steam condensers usually subcool the condensate to less than the saturation temperature, called condensate depression, to prevent cavitation in the condensate pumps.

If the head losses in the pump suction piping can be reduced, the NPSHA will be increased. Various methods for reducing head losses include increasing the pipe diameter, reducing the number of elbows, valves, and fittings in the pipe, and decreasing the length of the pipe.

It may also be possible to stop cavitation by reducing the NPSHR for the pump. The NPSHR is not a constant for a given pump under all conditions, but depends on certain factors. Typically, the NPSHR of a pump increases significantly as flow rate through the pump increases. Therefore, reducing the flow rate through a pump by throttling a discharge valve decreases NPSHR. NPSHR is also dependent upon pump speed. The faster the impeller of a pump rotates, the greater the NPSHR. Therefore, if the speed of a variable speed centrifugal pump is reduced, the NPSHR of the pump decreases. However, since a pump's flow rate is most often dictated by the needs of the system on which it is connected, only limited adjustments can be made without starting additional parallel pumps, if available.

The net positive suction head required to prevent cavitation is determined through testing by the pump manufacturer and depends upon factors including type of impeller inlet, impeller design, pump flow rate, impeller rotational speed, and the type of liquid being pumped. The manufacturer typically supplies curves of NPSHR as a function of pump flow rate for a particular liquid (usually water) in the vendor manual for the pump.

Centrifugal Pump Characteristic Curves

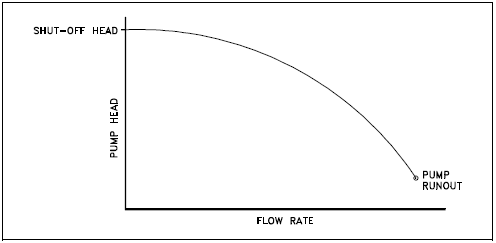

For a given centrifugal pump operating at a constant speed, the flow rate through the pump is dependent upon the differential pressure or head developed by the pump. The lower the pump head, the higher the flow rate. A vendor manual for a specific pump usually contains a curve of pump flow rate versus pump head called a pump characteristic curve. After a pump is installed in a system, it is usually tested to ensure that the flow rate and head of the pump are within the required specifications. A typical centrifugal pump characteristic curve is shown in Figure 11.

There are several terms associated with the pump characteristic curve that must be defined. Shutoff head is the maximum head that can be developed by a centrifugal pump operating at a set speed. Pump runout is the maximum flow that can be developed by a centrifugal pump without damaging the pump. Centrifugal pumps must be designed and operated to be protected from the conditions of pump runout or operating at shutoff head. Additional information may be found in the handbook on Thermodynamics, Heat Transfer, and Fluid Flow.

Centrifugal Pump Protection

A centrifugal pump is dead-headed when it is operated with no flow through it, for example, with a closed discharge valve or against a seated check valve. If the discharge valve is closed and there is no other flow path available to the pump, the impeller will churn the same volume of water as it rotates in the pump casing. This will increase the temperature of the liquid (due to friction) in the pump casing to the point that it will flash to vapor. The vapor can interrupt the cooling flow to the pump's packing and bearings, causing excessive wear and heat. If the pump is run in this condition for a significant amount of time, it will become damaged.

When a centrifugal pump is installed in a system such that it may be subjected to periodic shutoff head conditions, it is necessary to provide some means of pump protection. One method for protecting the pump from running dead-headed is to provide a recirculation line from the pump discharge line upstream of the discharge valve, back to the pump's supply source. The recirculation line should be sized to allow enough flow through the pump to prevent overheating and damage to the pump. Protection may also be accomplished by use of an automatic flow control device.

Centrifugal pumps must also be protected from runout. Runout can lead to cavitation and can also cause overheating of the pump's motor due to excessive currents. One method for ensuring that there is always adequate flow resistance at the pump discharge to prevent excessive flow through the pump is to place an orifice or a throttle valve immediately downstream of the pump discharge. Properly designed piping systems are very important to protect from runout.

Gas Binding

Gas binding of a centrifugal pump is a condition where the pump casing is filled with gases or vapors to the point where the impeller is no longer able to contact enough fluid to function correctly. The impeller spins in the gas bubble, but is unable to force liquid through the pump. This can lead to cooling problems for the pump's packing and bearings. Centrifugal pumps are designed so that their pump casings are completely filled with liquid during pump operation. Most centrifugal pumps can still operate when a small amount of gas accumulates in the pump casing, but pumps in systems containing dissolved gases that are not designed to be self-venting should be periodically vented manually to ensure that gases do not build up in the pump casing.

Priming Centrifugal Pumps

Most centrifugal pumps are not self-priming. In other words, the pump casing must be filled with liquid before the pump is started, or the pump will not be able to function. If the pump casing becomes filled with vapors or gases, the pump impeller becomes gas-bound and incapable of pumping. To ensure that a centrifugal pump remains primed and does not become gas-bound, most centrifugal pumps are located below the level of the source from which the pump is to take its suction. The same effect can be gained by supplying liquid to the pump suction under pressure supplied by another pump placed in the suction line.

Positive Displacement Pumps

Positive displacement pumps operate on a different principle than centrifugal pumps. Positive displacement pumps physically entrap a quantity of liquid at the suction of the pump and push that quantity out the discharge of the pump.

Introduction

A positive displacement pump is one in which a definite volume of liquid is delivered for each cycle of pump operation. This volume is constant regardless of the resistance to flow offered by the system the pump is in, provided the capacity of the power unit driving the pump or pump component strength limits are not exceeded. The positive displacement pump delivers liquid in separate volumes with no delivery in between, although a pump having several chambers may have an overlapping delivery among individual chambers, which minimizes this effect. The positive displacement pump differs from centrifugal pumps, which deliver a continuous flow for any given pump speed and discharge resistance.

Positive displacement pumps can be grouped into three basic categories based on their design and operation. The three groups are reciprocating pumps, rotary pumps, and diaphragm pumps.

Principle of Operation

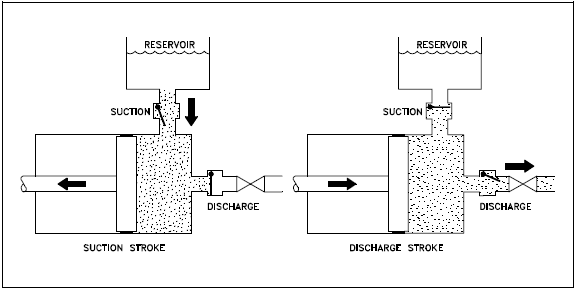

All positive displacement pumps operate on the same basic principle. This principle can be most easily demonstrated by considering a reciprocating positive displacement pump consisting of a single reciprocating piston in a cylinder with a single suction port and a single discharge port as shown in Figure 12. Check valves in the suction and discharge ports allow flow in only one direction.

During the suction stroke, the piston moves to the left, causing the check valve in the suction line between the reservoir and the pump cylinder to open and admit water from the reservoir. During the discharge stroke, the piston moves to the right, seating the check valve in the suction line and opening the check valve in the discharge line. The volume of liquid moved by the pump in one cycle (one suction stroke and one discharge stroke) is equal to the change in the liquid volume of the cylinder as the piston moves from its farthest left position to its farthest right position.

Reciprocating Pumps

Reciprocating positive displacement pumps are generally categorized in four ways: direct-acting or indirect-acting; simplex or duplex; single-acting or double-acting; and power pumps.

Direct-Acting and Indirect-Acting Pumps

Some reciprocating pumps are powered by prime movers that also have reciprocating motion, such as a reciprocating pump powered by a reciprocating steam piston. The piston rod of the steam piston may be directly connected to the liquid piston of the pump or it may be indirectly connected with a beam or linkage. Direct-acting pumps have a plunger on the liquid (pump) end that is directly driven by the pump rod (also the piston rod or extension thereof) and carries the piston of the power end. Indirect-acting pumps are driven by means of a beam or linkage connected to and actuated by the power piston rod of a separate reciprocating engine.

Simplex and Duplex Pumps

A simplex pump, sometimes referred to as a single pump, is a pump having a single liquid (pump) cylinder. A duplex pump is the equivalent of two simplex pumps placed side by side on the same foundation.

The driving of the pistons of a duplex pump is arranged in such a manner that when one piston is on its upstroke the other piston is on its downstroke, and vice versa. This arrangement doubles the capacity of the duplex pump compared to a simplex pump of comparable design.

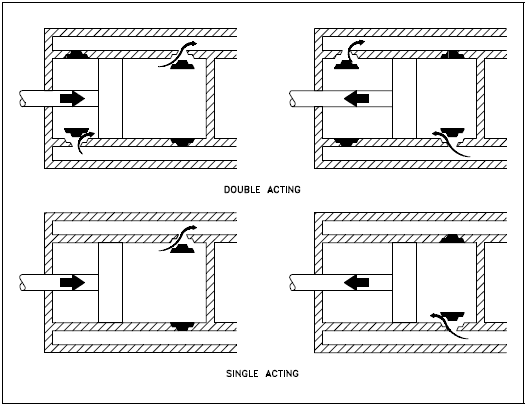

Single-Acting and Double-Acting Pumps

A single-acting pump is one that takes a suction, filling the pump cylinder on the stroke in only one direction, called the suction stroke, and then forces the liquid out of the cylinder on the return stroke, called the discharge stroke. A double-acting pump is one that, as it fills one end of the liquid cylinder, is discharging liquid from the other end of the cylinder. On the return stroke, the end of the cylinder just emptied is filled, and the end just filled is emptied. One possible arrangement for single-acting and double-acting pumps is shown in Figure 13.

Power Pumps

Power pumps convert rotary motion to low speed reciprocating motion by reduction gearing, a crankshaft, connecting rods and crossheads. Plungers or pistons are driven by the crosshead drives. Rod and piston construction, similar to duplex double-acting steam pumps, is used by the liquid ends of the low pressure, higher capacity units. The higher pressure units are normally single-acting plungers, and usually employ three (triplex) plungers. Three or more plungers substantially reduce flow pulsations relative to simplex and even duplex pumps.

Power pumps typically have high efficiency and are capable of developing very high pressures. They can be driven by either electric motors or turbines. They are relatively expensive pumps and can rarely be justified on the basis of efficiency over centrifugal pumps. However, they are frequently justified over steam reciprocating pumps where continuous duty service is needed due to the high steam requirements of direct-acting steam pumps.

In general, the effective flow rate of reciprocating pumps decreases as the viscosity of the fluid being pumped increases because the speed of the pump must be reduced. In contrast to centrifugal pumps, the differential pressure generated by reciprocating pumps is independent of fluid density. It is dependent entirely on the amount of force exerted on the piston. For more information on viscosity, density, and positive displacement pump theory, refer to the handbook on Thermodynamics, Heat Transfer, and Fluid Flow.

Rotary Pumps

Rotary pumps operate on the principle that a rotating vane, screw, or gear traps the liquid in the suction side of the pump casing and forces it to the discharge side of the casing. These pumps are essentially self-priming due to their capability of removing air from suction lines and producing a high suction lift. In pumps designed for systems requiring high suction lift and selfpriming features, it is essential that all clearances between rotating parts, and between rotating and stationary parts, be kept to a minimum in order to reduce slippage. Slippage is leakage of fluid from the discharge of the pump back to its suction.

Due to the close clearances in rotary pumps, it is necessary to operate these pumps at relatively low speed in order to secure reliable operation and maintain pump capacity over an extended period of time. Otherwise, the erosive action due to the high velocities of the liquid passing through the narrow clearance spaces would soon cause excessive wear and increased clearances, resulting in slippage.

There are many types of positive displacement rotary pumps, and they are normally grouped into three basic categories that include gear pumps, screw pumps, and moving vane pumps.

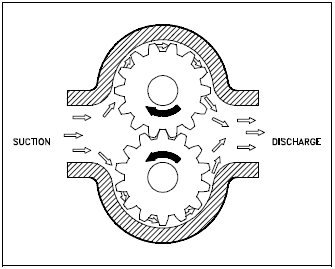

Simple Gear Pump

There are several variations of gear pumps. The simple gear pump shown in Figure 14 consists of two spur gears meshing together and revolving in opposite directions within a casing. Only a few thousandths of an inch clearance exists between the case and the gear faces and teeth extremities. Any liquid that fills the space bounded by two successive gear teeth and the case must follow along with the teeth as they revolve. When the gear teeth mesh with the teeth of the other gear, the space between the teeth is reduced, and the entrapped liquid is forced out the pump discharge pipe. As the gears revolve and the teeth disengage, the space again opens on the suction side of the pump, trapping new quantities of liquid and carrying it around the pump case to the discharge. As liquid is carried away from the suction side, a lower pressure is created, which draws liquid in through the suction line.

With the large number of teeth usually employed on the gears, the discharge is relatively smooth and continuous, with small quantities of liquid being delivered to the discharge line in rapid succession. If designed with fewer teeth, the space between the teeth is greater and the capacity increases for a given speed; however, the tendency toward a pulsating discharge increases. In all simple gear pumps, power is applied to the shaft of one of the gears, which transmits power to the driven gear through their meshing teeth.

There are no valves in the gear pump to cause friction losses as in the reciprocating pump. The high impeller velocities, with resultant friction losses, are not required as in the centrifugal pump. Therefore, the gear pump is well suited for handling viscous fluids such as fuel and lubricating oils.

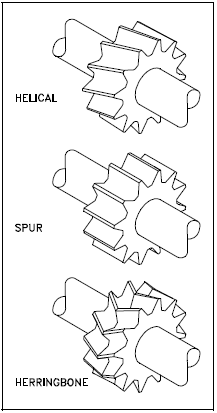

Other Gear Pumps

There are two types of gears used in gear pumps in addition to the simple spur gear. One type is the helical gear. A helix is the curve produced when a straight line moves up or down the surface of a cylinder. The other type is the herringbone gear. A herringbone gear is composed of two helixes spiraling in different directions from the center of the gear. Spur, helical, and herringbone gears are shown in Figure 15.

The helical gear pump has advantages over the simple spur gear. In a spur gear, the entire length of the gear tooth engages at the same time. In a helical gear, the point of engagement moves along the length of the gear tooth as the gear rotates. This makes the helical gear operate with a steadier discharge pressure and fewer pulsations than a spur gear pump.

The herringbone gear pump is also a modification of the simple gear pump. Its principal difference in operation from the simple spur gear pump is that the pointed center section of the space between two teeth begins discharging before the divergent outer ends of the preceding space complete discharging. This overlapping tends to provide a steadier discharge pressure. The power transmission from the driving to the driven gear is also smoother and quieter.

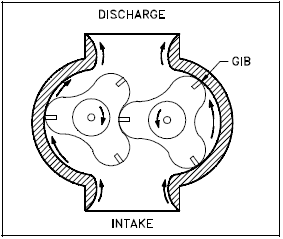

Lobe Type Pump

The lobe type pump shown in Figure 16 is another variation of the simple gear pump. It is considered as a simple gear pump having only two or three teeth per rotor; otherwise, its operation or the explanation of the function of its parts is no different. Some designs of lobe pumps are fitted with replaceable gibs, that is, thin plates carried in grooves at the extremity of each lobe where they make contact with the casing. The gib promotes tightness and absorbs radial wear.

Screw-Type Positive Displacement Rotary Pump

There are many variations in the design of the screw type positive displacement, rotary pump. The primary differences consist of the number of intermeshing screws involved, the pitch of the screws, and the general direction of fluid flow. Two common designs are the two-screw, low-pitch, double-flow pump and the three-screw, high-pitch, double-flow pump.

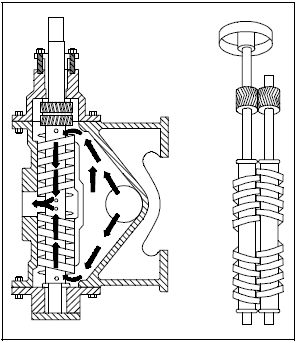

Two-Screw, Low-Pitch, Screw Pump

The two-screw, low-pitch, screw pump consists of two screws that mesh with close clearances, mounted on two parallel shafts. One screw has a right-handed thread, and the other screw has a left-handed thread. One shaft is the driving shaft and drives the other shaft through a set of herringbone timing gears. The gears serve to maintain clearances between the screws as they turn and to promote quiet operation. The screws rotate in closely fitting duplex cylinders that have overlapping bores. All clearances are small, but there is no actual contact between the two screws or between the screws and the cylinder walls.

The complete assembly and the usual flow path are shown in Figure 17. Liquid is trapped at the outer end of each pair of screws. As the first space between the screw threads rotates away from the opposite screw, a one-turn, spiral-shaped quantity of liquid is enclosed when the end of the screw again meshes with the opposite screw. As the screw continues to rotate, the entrapped spiral turns of liquid slide along the cylinder toward the center discharge space while the next slug is being entrapped. Each screw functions similarly, and each pair of screws discharges an equal quantity of liquid in opposed streams toward the center, thus eliminating hydraulic thrust. The removal of liquid from the suction end by the screws produces a reduction in pressure, which draws liquid through the suction line.

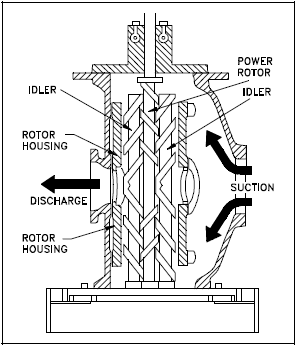

Three-Screw, High-Pitch, Screw Pump

The three-screw, high-pitch, screw pump, shown in Figure 18, has many of the same elements as the two-screw, low-pitch, screw pump, and their operations are similar. Three screws, oppositely threaded on each end, are employed. They rotate in a triple cylinder, the two outer bores of which overlap the center bore. The pitch of the screws is much higher than in the low pitch screw pump; therefore, the center screw, or power rotor, is used to drive the two outer idler rotors directly without external timing gears. Pedestal bearings at the base support the weight of the rotors and maintain their axial position. The liquid being pumped enters the suction opening, flows through passages around the rotor housing, and through the screws from each end, in opposed streams, toward the center discharge. This eliminates unbalanced hydraulic thrust. The screw pump is used for pumping viscous fluids, usually lubricating, hydraulic, or fuel oil.

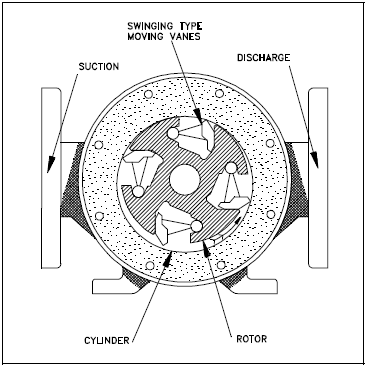

Rotary Moving Vane Pump

The rotary moving vane pump shown in Figure 19 is another type of positive displacement pump used. The pump consists of a cylindrically bored housing with a suction inlet on one side and a discharge outlet on the other. A cylindrically shaped rotor with a diameter smaller than the cylinder is driven about an axis placed above the centerline of the cylinder. The clearance between rotor and cylinder is small at the top but increases at the bottom. The rotor carries vanes that move in and out as it rotates to maintain sealed spaces between the rotor and the cylinder wall. The vanes trap liquid or gas on the suction side and carry it to the discharge side, where contraction of the space expels it through the discharge line. The vanes may swing on pivots, or they may slide in slots in the rotor.

Diaphragm Pumps

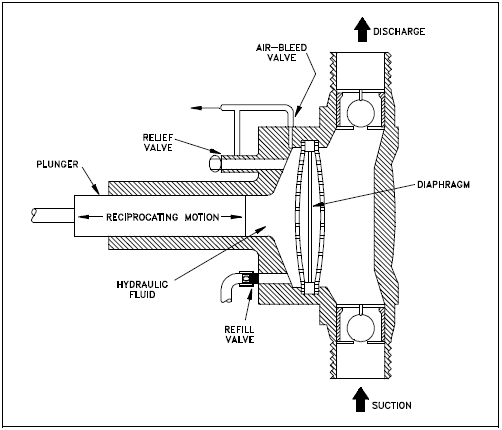

Diaphragm pumps are also classified as positive displacement pumps because the diaphragm acts as a limited displacement piston. The pump will function when a diaphragm is forced into reciprocating motion by mechanical linkage, compressed air, or fluid from a pulsating, external source. The pump construction eliminates any contact between the liquid being pumped and the source of energy. This eliminates the possibility of leakage, which is important when handling toxic or very expensive liquids. Disadvantages include limited head and capacity range, and the necessity of check valves in the suction and discharge nozzles. An example of a diaphragm pump is shown in Figure 20.

Positive Displacement Pump Characteristic Curves

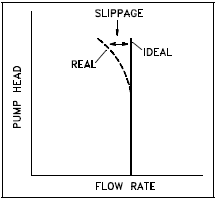

Positive displacement pumps deliver a definite volume of liquid for each cycle of pump operation. Therefore, the only factor that effects flow rate in an ideal positive displacement pump is the speed at which it operates. The flow resistance of the system in which the pump is operating will not effect the flow rate through the pump. Figure 21 shows the characteristic curve for a positive displacement pump.

The dashed line in Figure 21 shows actual positive displacement pump performance. This line reflects the fact that as the discharge pressure of the pump increases, some amount of liquid will leak from the discharge of the pump back to the pump suction, reducing the effective flow rate of the pump. The rate at which liquid leaks from the pump discharge to its suction is called slippage.

Positive Displacement Pump Protection

Positive displacement pumps are normally fitted with relief valves on the upstream side of their discharge valves to protect the pump and its discharge piping from overpressurization. Positive displacement pumps will discharge at the pressure required by the system they are supplying. The relief valve prevents system and pump damage if the pump discharge valve is shut during pump operation or if any other occurrence such as a clogged strainer blocks system flow.